The 2010s decade is drawing to a close and we look back at the most important cyber-security events that have taken place during the past ten years.

Over the past decade, we’ve seen it all. We’ve had monstrous data breaches, years of prolific hacktivism, plenty of nation-state cyber-espionage operations, almost non-stop financially-motivated cybercrime, and destructive malware that has rendered systems unusable.

Below is a summary of the most important events of the 2010s, ordered by year. We didn’t necessarily look at the biggest breaches or the most extensive hacking operations but instead focused on hacks and techniques that gave birth to a new cyber-security trend or were a paradigm shift in how experts looked at the entire field of cyber-security.

From the Stuxnet attacks of 2010 to China’s extensive mass-surveillance of the Uyghur minority, we selected the most relevant events and explained why they were important.

2010

Stuxnet

Stuxnet is a computer worm that was co-developed by the US and Israeli intelligence services as a means to sabotage Iran’s nuclear weapons program, which was getting off the ground in the late 2000s.

The worm was specifically designed to destroy SCADA equipment used by the Iranian government in its nuclear fuel enrichment processes. The attack was successful, destroyng equipment in several locations.

While there have been other cyber-attacks carried out by nation-states against each other prior to 2010, Stuxnet was the first incident that grabbed headlines across the world and marked the entry into a new phase of cyber-war — from simple data theft and information gathering to actual physical destruction.

More on Stuxnet’s impact and operation can be found in Kim Zetter’s “Countdown to Zero Day” book and the “Zero Days” documentary.

Operation Aurora – the Google hack

Not that many internet users know that even the mighty Google had its backend infrastructure hacked.

It was part of a series of attacks that later become known as Operation Aurora — a coordinated hacking campaign carried by the Chinese government’s military hackers against some of the world’s biggest companies at the time, like Adobe, Rackspace, Juniper, Yahoo, Symantec, Northrop Grumman, Morgan Stanley, and others. The actual attacks took place in the 2000s, however, they came to light in early 2010.

Operation Aurora was a turning point in Google’s history. After Google discovered and publicly disclosed the attacks, the company decided to stop working with the Chinese government in censoring search results for Google.cn, and Google eventually shut down operations in China soon after. The Operation Aurora cyber-attack was specifically mentioned as one of the reasons behind Google’s move.

The “press release” hackers

Between 2010 and 2015, a group of five Eastern European men hacked several newswire services from where they stole soon-to-be-announced press releases.

Sounds like a waste of time? No, it definitely wasn’t. It was actually one of the smartest hacks of the decade because the group used the insider information they got to anticipate stock market shifts and place trades that netted more than $100 million in profits.

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) and the US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) eventually got wind of their scheme and cracked down on the group’s members starting with 2016.

The Verge has the best piece on the group, providing an inside look at the group’s operation.

2011

LulzSec and the “50 days of luls”

Every time you see a hacker bragging on Twitter about their hacks, using a broad array of internet memes to make fun of their targets, or taking suggestions on who to DDoS or hack, you’re seeing another LulzSec copycat.

The group’s impact on today’s hacking scene cannot be ignored. The group liked to hack big-name companies and then showboat all over the internet.

Their “50 days of lulz” campaign and all the other major hacks they carried out set the trend for what we ended up seeing for the rest of the decade from a slew of copycat attention-seeking hacking groups, such as Lizard Squad, New World Hackers, TeaMp0isoN, CWA, and others. However, LulzSec remains atop everyone else primarily due to their impressive list of hacked targets, which includes Fox, HBGary, PBS, the CIA, and Sony.

Diginotar hack changes the browser landscape

The hack of DigiNotar is a little known incident from 2011 that ended up changing how browsers, Certificate Authorities (CAs), and the internet works — and for the better.

In 2011, it was discovered that Iranian government hackers breached DigiNotar and used its infrastructure to issue SSL certificates for mimicking popular websites, including Google and Gmail. Iranian hackers then used the certificates to intercept encrypted HTTPS traffic and spy on more than 300,000 Iranians.

An investigation revealed appalling security and business practices at the Dutch company, which in turn led to a blanket ban across browsers, which refused to verify HTTPS websites secured with DigiNotar certificates.

The hack made Google, browser makers, and other tech giants take notice, and led to an overhaul for the entire practice of issuing SSL/TLS certificates. Many of the procedures put in place following the DigiNotar hack are in use even today.

Sony PlayStation hack and massive outage

In the spring of 2011, Sony announced that a hacker stole details for 77 million PlayStation Network users, including personally identifiable information and financial details.

Nowadays, this might seem an insignificant number, but at the time, and for many years after, this was one of the biggest hack in the world.

For Sony, this hack was catastrophic, to say the least. The company had to shut down its cash cow — the Sony PlayStation Network — for 23 days while engineers addressed the security breach. To this day, this still remains the longest outage in PSN’s history.

The company lost profits due to the outage, but also because of class-action lawsuits filed by users after some started noticing credit card fraud. It then also lost even more money when it had to give users a bunch of free PlayStation 3 games to get them back online.

The Sony PSN 2011 hack stands out because it showed the damages a hack could cause if a company fails to invest in proper security. It also stands out because it started a trend of companies adding clauses to their Terms of Service that force users to give up on their right to file lawsuits following security breaches. Sony wasn’t the first to use such a clause, but they made it popular, and many other companies added a similar clause soon after.

2012

Shamoon and its destruction

Created in Iran, Shamoon (also known as DistTrack) is a piece of malware that can be considered the direct result of the Stuxnet attack from two years before.

Having learned first hand how destructive malware can be, the Iranian government created its own “cyber-weapon,” one that it first deployed in 2012.

Designed to wipe data, Shamoon destroyed more than 35,000 workstations on the network of Saudi Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, bringing the company to its knees for weeks. It was reported at the time that Saudi Aramco purchased most of the hard drives in the wolrd in its effort to replace its destroyed PC fleet, driving HDD prices up for months after, while vendors struggled to keep up with demand.

Versions of the malware were spotted in subsequent years, mostly deployed in companies active or associated with the oil and gas industry.

Flame – the most sophisticated malware strain ever created

Discovered by Kaspersky and linked to the Equation Group (a codename for the US NSA), Flame was described as the most advanced and sophisticated malware strain ever created.

It eventually lost this title when Kaspersky found Regin two years later in 2014, but Flame’s discovery revealed the technical and capabilities gap between the cyber arsenal of the United States and all the other tools employed by other nation-state groups.

A subsequent report by the Washington Times claimed that Flame was part of the same arsenal of hacking tools as Stuxnet, and was primarily deployed against Iran. The malware hasn’t been sighted since but it’s discovery is still considered today as a major point in the escalation of cyber-espionage operations all over the world.

2013

Snowden revelations

So much to say, so little space. We’ll just get to the point. The Snowden leaks are probably the most important cyber-security event of the decade. They exposed a global surveillance network that the US and its Five Eyes partners had set up after the 9/11 attacks.

Snowden’s revelations led countries like China, Russia, and Iran to create their own surveillance operations and amp up foreign intelligence-gathering efforts, leading to an increase in cyber-espionage as a whole.

Currently, many countries flaunt concepts like a “national internet” or “internet sovereignty” to justify spying on their citizens and censoring the web — and it all started after Snowden revealed to the world the NSA’s dirty laundry back in 2013.

The Wikipedia page is pretty complete on the impact of Snowden’s leaks, which is a good point for anyone to start researching the subject.

The Target hack

In December 2013, the world was introduced to the term of POS malware when retail giant Target admitted that malware planted on its stores’ systems had helped hackers collected payment card details for roughly 40 million users.

Incidents of POS malware had happened before, but this was the first time when a major retailer suffered a breach of these proportions.

Other retailers would follow in the next years, and through dogged reporting, the world would eventually find out how hackers trade stolen cards on sites called “card shops” to create cloned cards and empty users’ bank accounts.

The Adobe hack

In November 2013, Adobe admitted that hackers had stolen the data of more than 153 million users. The data was dumped online, and user passwords were almost immediately cracked and reversed back to their plaintext versions.

For many years to come, the incident was used to push for the adoption of strong password hashing functions.

Silk Road takedown

Silk Road was the first major takedown of a Tor-hosted dark web marketplace for selling illegal products. Its takedown in 2013 showed the world for the first time that the dark web and Tor weren’t perfect, and that the law’s arm could reach even in this corner of the internet, thought to have been impenetrable up to that point.

Other marketplaces popped up like mushrooms after Silk Road’s takedown, but none survived for long. Most of them either exit scammed (admins ran away with users’ money) or were also eventually taken down by law enforcement as well.

Have I Been Pwned?

Launched in December 2013 and built around the idea of giving users a simple way to check if they’ve been included in the Adobe breach, the Have I Been Pwned website is today a brand on its own.

The site still works like when it launched and allows users to see if their usernames or emails have been included in a data breach.

Currently, the site includes databases from over 410 hacked sites and information on more than 9 billion accounts. It is integrated in Firefox, password managers, company backends, and even some government systems.

Managed by Australian security expert Troy Hunt, the site has greatly contributed to improving the security posture of organizations all over the world.

2014

North Korea’s brazen Sony hack

Without a doubt, the hack of Sony Pictures in 2014 is the first time when the world learned that North Korea has hackers and pretty good ones at it.

The hacks were carried out by a group calling themselves the Guardians of Peace (subsequently referred to as the Lazarus Squad) that were eventually linked to North Korea’s intelligence apparatus.

The purpose of the hack was to force the studio to abandon releasing a movie called The Interview, a comedy about an assassination plot against North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un.

When Sony refused, hackers destroyed the company’s internal network and leaked studio data and private emails online.

The Sony incident — deemed nothing more than a petty hack — helped cyber-security firms understand the scope and spread of North Korea’s hacking abilities, insight they’d eventually call upon in the following years, for numerous other incidents.

Prior to this incident, North Korean hackers were primarily focused on hacking their southern neighbors. Following the hack and the sanctions imposed by President Obama, their hacking operations spread globally, making the country one of today’s most active cyber-espionage and cybercrime players.

Celebgate

To this day, cyber-security companies use Celebgate (also known as The Fappening) as an example in training courses about spear-phishing, and what happens when users don’t pay attention to the validity of password reset emails.

This is because back in 2014, a small community of hackers used fake password reset emails aimed at celebrities to gain access to trick famous stars into entering their Gmail or iCloud passwords on phishing sites.

The hackers used these credentials to access accounts, find sexual or nude images and videos, which they later dumped online. Other “Fappening” waves took place in later years, but the original set of leaks took place in the summer of 2014.

Carbanak starts hacking banks

For many years, experts and users alike thought that hackers seeking money would generally go after consumers, store retailers, or companies.

The reports on Carbanak (also known as Anunak or FIN7) showed for the first time the existence of a highly skilled hacker group that was capable of stealing money directly from the source — namely, the banks.

Reports from Kaspersky Lab, Fox-IT, and Group-IB showed that the Carbanak group was so advanced it could penetrate banks’ internal network, stay hidden for weeks or months, and then steal huge amounts of money, either via SWIFT bank transactions or coordinated ATM cashouts.

In total, the group is thought to have stolen more than $1 billion from hacked banks, a figure that has yet to be matched by any other group.

Mt. Gox hack

Mt. Gox was not the first cryptocurrency exchange in the world to get hacked, but it remains the biggest cyber-heist of the cryptocurrency ecosystem to this day.

The hack, still surrounded in mystery today, occurred in early 2014, when hackers made off with 850,000 bitcoins, worth more than $6.3 billion today. At the time, Mt. Gox was the biggest cryptocurrency exchange in the world.

Following this incident, hackers realized they could make huge profits by targeting exchange platforms due to their weaker security protections when compared to real-world banks. Hundreds of other hacks followed in the subsequent years, but Mt. Gox still stands as the incident that sparked the ensuing onslaught.

Phineas Fisher

The summer of 2014 is when the world first learned of Phineas Fisher, a hacktivist who liked to breach companies that make spyware and surveillance tools.

The hacker breached Gamma Group in 2014 and HackingTeam in 2015. From both, the hacker published internal documents and source code for the companies’ spyware tools, and even some zero-days.

Phineas’ leaks helped exposed the shadowy world of companies that sell hacking, spyware, and surveillance tools to governments across the world. While some tools were arguably used to catch criminals, some of the sales were linked to oppressive regimes who abused them to spy on dissidents, journalists, and political opponents.

Heartbleed

The Heartbleed vulnerability in OpenSSL is one of those rare security flaws that are just too good to be true.

The bug allowed attackers to retrieve cryptographic keys from public servers, keys they could use to decrypt traffic or authenticate on vulnerable systems.

It was exploited within days after being publicly disclosed, and led to a long string of hacks in 2014 and beyond, as some server operators failed to patch their OpenSSL instances, despite repeated warnings.

At the time it was publicly disclosed, it was believed that about half a million internet servers were vulnerable, a number which took years to bring down.

2015

Ashley Madison data breach

There have been thousands of data breaches in the past decade, but if ZDNet would have to choose the most important one, we’d choose the Ashley Madison 2015 breach without batting an eye or a second thought.

The breach took place in July 2015 when a hacker group calling themselves the Impact Team released the internal database of Ashley Madison, a dating website marketing itself as a go-to place for having an affair.

Most breaches today expose your username and password on forums you don’t even remember registering on in the early 2000s. But this was not the case with the Ashley Madison breach, which exposed many people’s dirty laundry as no other breach had ever done.

Users registered on the site faced extortion attempts, and some committed suicide after being publicly outed as having an account on the site. It is one of the few cyber-security incidents that led directly to someone’s death.

Anthem and OPM hacks

Both hacks were disclosed in 2015 — Anthem in February and the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM) in June — and were carried out by Chinese hackers backed by the Beijing government.

They stole 78.8 million medical records from Anthem and 21.5 million records for US government workers.

The two hacks are the crown jewel of a series of hacks the Chinese government perpetrated against the US, for the purpose of intelligence gathering. The video below, at 27:55, provides some insight into how some of the data stolen from these two organizations could have been used to expose CIA agents, among many other things. The hacks signaled the rise of China as a threat actor on the global stage just as sophisticated and advanced as the US and Russia. Prior to that, Chinese hackers were considered unskilled, following a smash-and-grab approach of stealing everything they could get their hands on. Today, Chinese hackers are used as surgical knives part of the Chinese government’s plan to advance its economy and local companies.

SIM swapping

SIM swapping refers to a tactic where hackers call a mobile telco and trick the mobile operators into transferring a victim’s phone number to a SIM card controlled by the attacker.

Reports about attacks where SIM swapping was first used date back to 2015. Initially, most SIM swapping attacks were linked to incidents where hackers reset passwords on social media accounts, hijacked sought-after usernames, which they later resold online.

SIM swapping attacks grew in popularity as hackers slowly realized they could also use the technique to gain access to cryptocurrency or bank accounts, from where they could steal large sums of money.

Since then, the technique has become more and more prevalent, with US telcos being most susceptible to attacks due to their unwillingness to prevent users from being able to migrate phone numbers without an in-person visit to one of their stores, as it’s done in most parts of the world.

DD4BC & Armada Collective

2015 is also the year where DDoS extortion demands became a thing. The technique was pioneered and made popular by a group named DD4BC that would send emails to companies demanding payment in Bitcoin, or they’d attack the company’s infrastructure with DDoS attacks and take down crucial services.

Europol arrested this original group’s members back in early 2016, but DD4BC’s modus operandi was copied by a group calling themselves Armada Collective, who made the practice even more popular.

The tactics DD4BC and Armada Collective first used back in 2015 and 2016 are still used even today, being at the heart of many of today’s DDoS attacks, and the downtime they incur on some targets.

The Ukraine power grid hacks

The cyber-attack on Ukraine power grid in December 2015 caused power outages across western Ukraine and was the first successful attack on a power grid’s control network ever recorded.

The 2015 attack employed a piece of malware known as Black Energy and was followed by another similar attack the next year, in December 2016. This second attack used even a more complex piece of malware, known as Industroyer, and successfully cut off power to a fifth of Ukraine’s capital.

While Stuxnet and Shamoon were the first cyber-attacks against an industrial target, the two Ukraine incidents were the first ones that impacted the general public, and opened everyone’s eyes to the dangers cyber-attacks can pose to a country’s critical infrastructure.

These two attacks were just the beginning of a long string of hacks carried out by Russian hackers against Ukraine, following Russia’s invasion of the Crimea peninsula in early 2014. Other cyber-security incidents part of this include the NotPetya and Bad Rabbit ransomware outbreaks of 2017.

The group behind the attacks is referred to as Sandworm and is believed to be a section of Russia’s military intelligence apparatus. The book Sandworm, nd authored by Wired security editor Andy Greenberg, details this group’s hacking operations in greater detail.

2016

Bangladesh Bank cyber-heist

In February 2016, the world found out that hackers attempted to steal more than $1 billion from a Bangladeshi bank, only to be thwarted by a typo and only get away with $81 million.

While initially, everyone thought this was a bumbling hacker, it was later revealed that North Korea’s elite hackers were behind the attempted cyber-heist, which was only one of the many similar hacks they tried that year — successfully pulling others, in other countries.

The Bangladesh Bank hack had a huge impact on the banking sector, as a whole. Decisions made in the wake of the attempted hack resulted in comprehensive security updates to SWIFT, the international transaction system for moving funds between different banks. Second, the SWIFT organization also banned North Korea from its system, a decision that had repercussions in the years to come.

These two decisions together pushed Pyongyang hackers towards targeting cryptocurrency exchanges, from where they’re believed to have stolen hundreds of millions of US dollars, money the North Korean state used to build up its nuclear weapons program.

Panama Papers

In April 2016, a consortium of the world’s leading investigative journalists published extensive reports collectively named the Panama Papers that exposed how the world’s richest people, including businessmen, celebrities, and politicians, were using tax heavens to avoid paying income taxes.

The leak is considered the biggest of its kind and came from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. While journalists said they received the data from an anonymous source, many believe the data came from a hacker who exploited flaws in the law firm’s outdated WordPress and Drupal sites to gain access to its internal network.

DNC hack

Ah, the DNC hack. The hack that keeps on giving.

In the spring of 2016, the Democratic National Committee admitted it suffered a security breach after a hacker going by the name of Guccifer 2.0 started publishing emails and documents from the organization’s servers.

Through forensic evidence, it was later discovered that the DNC had been hacked not by one, but two Russian cyber-espionage groups, known as Fancy Bear (APT28) and Cozy Bear (APT29).

Data stolen during the hack was used in a carefully staged intelligence operation with the aim of influencing the upcoming US presidential election. If the entire affair succeeded or not, it can’t be said, although some will say that it did. However, the hack has dominated the news all year, and is still making waves even today, at the time of writing, in late November 2019, more than three years later.

Yahoo hacks go public

To say that 2016 was a bad year for Yahoo is an understatement. The company announced not one, but two data breaches in the span of four months, including what would turn out to be the largest breach in the history of the internet.

Both breaches are interconnected, in a weird way. Here’s a timeline, as things tend to be confusing:

- In July 2016, a hacker began selling Yahoo user data on the dark web.

- While investigating the validity of the hacker’s claims, Yahoo discovered and disclosed in September 2016 a breach that occurred in 2014, and impacted 500 million users.

- Yahoo blamed this breach on a “nation-state actor” and it eventually turned out be true. In 2017, US authorities charged a group of hackers for breaching Yahoo’s network at the behest of the Russian government.

- Ironically, while looking into the 2014 breach, Yahoo also tracked down the source of the user data that was being sold on the dark web.

- This was tracked down to a 2013 security breach that Yahoo said it initially impacted one billion users. In 2017, Yahoo updated the number to three billion — all its entire userbase — becoming the largest ever recorded data breach.

Year of the data dumps (Peace_of_mind)

But the two Yahoo breaches are just some of the few breaches that became public in 2016, which could be easily renamed into “the year of the data dumps.”

Companies who had old or new breaches pushed into the limelight include: Twitter, LinkedIn, Dropbox, MySpace, Tumblr, Fling.com, VK.com, OK.ru, Rambler.ru, AdultFriendFinder, Badoo, QIP, and many more.

More than 2.2 billion user records were exposed, and most were put up for sale on hacking forums and dark web marketplaces. Most of the breaches came to light via data traders like Peace_of_Mind, Tessa88, and LeakedSource.

The Shadow Brokers

Between August 2016 and April 2017, a group of hackers calling themselves The Shadow Brokers teased, auction, and then leaked hacking tools developed by the Equation Group, a codename for the US National Security Agency (NSA).

These tools were top-shelf quality hacking tools, and they made an immediate impact. A month after the final Shadow Brokers leak, one of the tools (an exploit for the Microsoft SMB protocol, known as EternalBlue) was used as the main engine behind the WannaCry global ransomware outbreak.

To this day, the world has not found out who the Shadow Brokers are.

Mirai and the IoT nightmare

A blog post in early September 2016 introduced the world to Mirai, a strain of Linux malware designed to work on routers and smart Internet of Things devices.

In the next 90 days, Mirai would become one of the most well-known malware strains in the world, after being used to launch some of the biggest DDoS attacks.

Mirai’s source code was released online, and it’s one of today’s most widespread malware family, with its code being at the base of most IoT/DDoS botnets.

Mirai single-handedly made everyone understand that the S in IoT stands for security.

2017

The three ransomware outbreaks

We can’t have this list without mentioning the three ransomware outbreaks of 2017 — namely WannaCry (mid-May), NotPetya (late June), and Bad Rabbit (late October).

All three were developed by government-backed hackers, but for different reasons.

WannaCry was developed by North Korean hackers looking to infect companies and extort ransom payments as part of an operation to raise funds for the sanctioned Pyongyang regime, while NotPetya and Bad Rabbit were cyber-weapons deployed to damage Ukrainian businesses as part of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

None of these entities meant to cause a global outbreak. The problem is that they relied on the EternalBlue exploit leaked moths before by the Shadow Brokers, an exploit that they didn’t fully understand at the time, and each ransomware strain spread far beyond what creators initially intended.

Ironically, despite being developed by the Russian government, NotPetya and Bad Rabbit ended up causing more damage to Russian businesses than companies in any other country, and this is most likely the reason why we haven’t seen another untethered ransomware outbreak since 2017.

Vault7 leaks

Vault7 was WikiLeaks’ last good leak. It was a trove of documentation files describing the CIA’s cyber-weapons.

No source code was ever included; however, the leak provided a look into the CIA’s technical capabilities, some of which included tools to hack iPhones, all the major desktop operating systems, the major browsers, and even smart TVs.

At the time, WikiLeaks said it received the Vault7 data trove from a whistleblower, who was later identified as Joshua Adam Schulte.

The MongoDB apocalypse

System administrators have been leaving databases exposed online without a password for years, but 2017 was the year when hackers finally started taxing admins and companies who did this.

Informally known as the MongoDB Apocalypse, it started in late December 2016, but picked up steam by January the next year, with hackers accessing databases, deleting their content, and leaving ransom notes behind, asking for cryptocurrency to return the (non-existent) data.

The first wave of attacks targeted exposed MongoDB servers, but hackers later expanded to other database technologies such as MySQL, Cassandra, Hadoop, Elasticsearch, PostgreSQL, and others.

Attacks died out by the end of the year, but they also brought into the public eye the problem of misconfigured databases that are being left online without protection.

By the end of the year, we had a new category of security researchers known as “breach hunters” — individuals who look for open databases and then contact companies to let them know they’re exposing sensitive information online.

In the subsequent years, most security breaches and data exposures were being discovered by breach hunters, rather than hackers dumping a company’s data online after an intrusion.

Equifax hack

Mystery still surrounds the Equifax hack of 2017, during which the personal details of more than 145.5 million Americans, British, and Canadian citizens were stolen from the company’s systems.

Although we have a post-mortem, and we know the breach was caused by the company failing to patch a critical server, we still don’t know who was behind the intrusion, or what were their motives — if it’s a cyber-espionage operation, or just good ol’ cybercrime.

Either way, hacking one of America’s three consumer credit reporting agencies gets you on any hack of the decade list.

Cryptojacking

The rise and fall of cryptojacking can be tied directly to Coinhive, a web service that made it feasible to mine cryptocurrency via JavaScript, as a file that could be added to any website.

Developed as an alternative to classic advertising, hacker groups took the idea and ran wild with it, placing cryptojacking scripts on any place that could run JavaScript — from hacked websites to video game modules, and from router control panels to browser extensions.

From September 2017 to March 2019, when Coinhive shut down, cryptojacking (also known as drive-by mining) was a scourge for internet users, slowing down browsers, and driving CPU usage through the roof, even if the technique wasn’t particularly profitable.

2018

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook’s fall from grace

While nobody particularly liked Facebook before 2018, most people who had a problem with the company usually complained about its timeline algorithms that buried friends posts under a heap of useless garbage or the slow-loading UI that seemed to get more crowded each day.

Then, Cambridge Analytica happened in early 2018, and the world had an actual reason to hate the social network and its data hoarding practices.

The scandal, just one of the many which would follow in the months to come, exposed how data analytics companies were abusing Facebook’s easy to grab user data to create profiles that they’d sell to political parties in order to sway public opinion and manipulate elections.

From a place were users would visit to keep in touch with friends, Facebook became in many people’s views the place where you’d be inundated with political propaganda disguised as internet memes and blatantly false information disguised as news articles.

The Great Hack is a great documentary to watch if you ever need an inside look at the whole scandal.

Meltdown, Spectre, and the CPU side-channel attacks

Details about the Meltdown and Spectre vulnerabilities were first made public on January 2, 2018, and they exposed an issue baked into the hardware of most CPUs that could allow hackers to steal data that was currently being processed inside CPUs.

While the two aren’t the easiest bugs to exploit, and nor has any attack ever been reported, Meltdown & Spectre exposed the fact that many CPU makers were cutting corners in terms of data security in their quest for speed and performance.

Even if some people still describe the two bugs as “stunt hacks,” they fundamentally changed how CPUs are designed and manufactured today.

Magecart goes mainstream

While Magecart attacks (also known as web skimming, or e-skimming) have been taking place since 2016, it was 2018 when attacks grew to a level where they were just impossible to miss — with high-profile hacks being reported by British Airways, Newegg, Inbenta, and others.

The scheme behind these attacks is simple, and it’s a mystery why they took so many years to become popular. The idea is that hackers compromise an online store, and leave behind malicious code that logs payment card information, which they later send back to an attacker’s server.

Several variations on the original Magecart attacks have appeared, but since early 2018, Magecart attacks are, without a doubt, one of today’s top cyber threats, and have been driving online shoppers mad, with many not being able to tell if an online shop is safe to use or not.

Next to ATM skiming and POS malware, Magecart attacks are the primary method through which cybercriminal groups are getting their hands on people’s financial data these days.

Marriott hack

Not as big as Yahoo’s three-billion figure, but the Marriott data breach also gets a nod due to its sheer size.

The breach was disclosed in November 2018, and impacted more than 500 million guests, a number which the company brought down to 383 million a few months later, after it finished its investigation.

Just like in most cases, a post-mortem revealed the company was breached using mundane tactics and tools that could have been easily detected and prevented.

2019

Uighur surveillance

2019 will be remembered as the year when China’s holocaustic tendencies came to light, with the revelations surrounding the way it treats its Uyghur Muslim minority in the Xinjiang region.

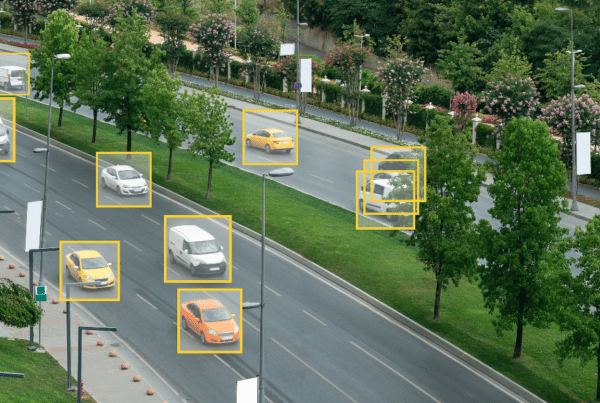

While news of organ harvesting and forced labor camps came to light in mainstream media, security researchers also played their part, revealing the widespread use of facial recognition software to track Muslims in Xinjiang cities, but also iOS, Android, and Windows exploits specifically targeted at infecting and tracking the local Uyghur population.

“Big game hunting” ransomware

While ransomware has been a problem all the 2010s, a particularly nasty form known as “big game hunting” has been extremely active in 2019.

Big game hunting refers to ransomware gangs who go only after big targets, such as corporate networks, rather than going after the little guy, like home users. This allows hackers to demand more money from victim companies, who have much more to lose than just personal photo albums.

The term big game hunting was coined by CrowdStrike in 2018 to describe the tactics of several ransomware gangs, and the number of groups currently engaging in this tactic has easily gone over ten.

Big game hunting ransomware attacks ramped up in 2019, with most hitting managed service providers, US schools, US local governments, and, more recently, moving to Europe’s bigger companies.

Gnosticplayers

The hacker who made a name for himself in 2019 is Gnosticplayers.

Following the modus operandi of Peace_of_Mind and Tessa88 from 2016, Gnosticplayers hacked companies and began selling their data on dark web marketplaces.

Companies that had their data stolen by Gnosticplayers and later put up for sale online include Canva, Gfycat, 500px, Evite, and many others. In total, the hacker claimed responsability for over 45 hacks and breaches impacting more than one billion users.

CapitalOne

The Capital One hack that was disclosed in July 2019 impacted more than 100 million Americans and six million Canadians.

Data from the breach is not believed to have been publicly shared en-masse, so most users who had their data stolen are most likely safe. Yet, the breach stands out because of the way it happened.

An investigation revealed that the suspect behind the hack was a former Amazon Web Services employee, who stands accused of illegally accessing Capital One’s AWS servers to retrieve the data, along with the data from 30 other companies.

The investigation is still ongoing, but if this turns out to be true, this introduces a new threat class for organizations — namely, malicious insiders working for your supply-chain providers.

About Crown Sterling Limited LLC

Leader in Data Sovereignty and provider of quantum-secure encryption, Crown Sterling empowers individuals and communities in an era of unregulated data consolidation, monopolization, and monetization by Big Tech. By leveraging next-generation encryption, blockchain technology, and decentralized digital transformation represented by Web3, we are committed to granting you complete control over your personal data and supporting the protection of free speech, assembly and choice.

The launch of Orion™ Messenger presents a quantum-secure end-to-end encrypted, uncensorable, and decentralized communications platform as a solution where sovereign individuals and communities can thrive. Unlike commonly used applications that rely on vulnerable encryption protocols, data mining practices, and other limitations, Orion is the only platform allowing for large encrypted group chat and social media communications in an unmonitored and uncensorable environment. Join the Orion Messenger waitlist.